Understanding Children's Dialogue in Writing

Let’s face it: Kids are a lot of work. No one would argue that point in the real world—no one who’s spent time around them, anyhow. And little ones can be just as much of a handful on the page. Especially when it comes to dialogue, making young characters believable can leave a thin margin for error. According to Novelists, Inc., writers often lean either too eloquent or too “cutesy” to make them sound authentic. In a guest post for the Jane Friedman writing blog, developmental editor Jessi Hoffman even ventures to say kids’ speech is some of the worst dialogue ever written.

For authors who interact with children regularly through their day jobs or via family and friends, writing dialogue is somewhat easier—as long as characters and their real-life counterparts are around the same age. But there’s a more consistent way to craft dialogue for children. Both the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) list benchmarks for children’s speech development based on their age. No need for extra babysitting gigs—just match your character’s dialogue to the proper language milestones listed below.

Birth to One Year

In the first few months of their life, babies don’t do much in the way of intelligent speech. At this stage, both ASHA and NIDCD list cooing, crying, giggling, and babbling as typical. Around six months old, children might also begin to use gestures, such as raising their arms to be lifted or waving bye, and they’ll start to understand the word “no” and their name, according to ASHA. Within their first year, according to NIDCD, they might also say their first word, though this would generally happen closer to their first birthday.

One Year Old

Children will begin to point to body parts when asked and may begin to ask simple questions themselves, such as “what?” or “where?” According to NIDCD, their vocabulary should grow to about fifty words, though they might not always be easily understood.

Two Years Old

Children have a word for almost everything by two years old, start to understand opposites and develop object permanence. They’ll also begin to ask the dreaded “why?” Their speech may still leave off some ending sounds, according to NIDCD, but they can generally be understood by their family or those close to them.

Three Years Old

Toddlers begin to match rhyming words and separate things into groups around three years old. They’ll use pronouns like “I,” “me,” “you,” or “they” and start to express ideas and feelings rather than just make visual observations. According to NIDCD, at this stage, children will start to have fun with language and recognize silly statements in books or jokes.

Four Years Old

Children will begin to tell stories and answer complex questions. Their speech is understandable, though they might still make some mistakes when pronouncing long words—think about how Nemo struggles with “anemone” in Finding Nemo. They’ll use some irregular past tense verbs at this stage, so try to avoid the misplaced “-ed” endings on words like “fall” or “sit.” They’ll also speak differently with different people, using shorter and simpler sentences with younger children while asking adults more complicated, inquisitive questions, according to ASHA.

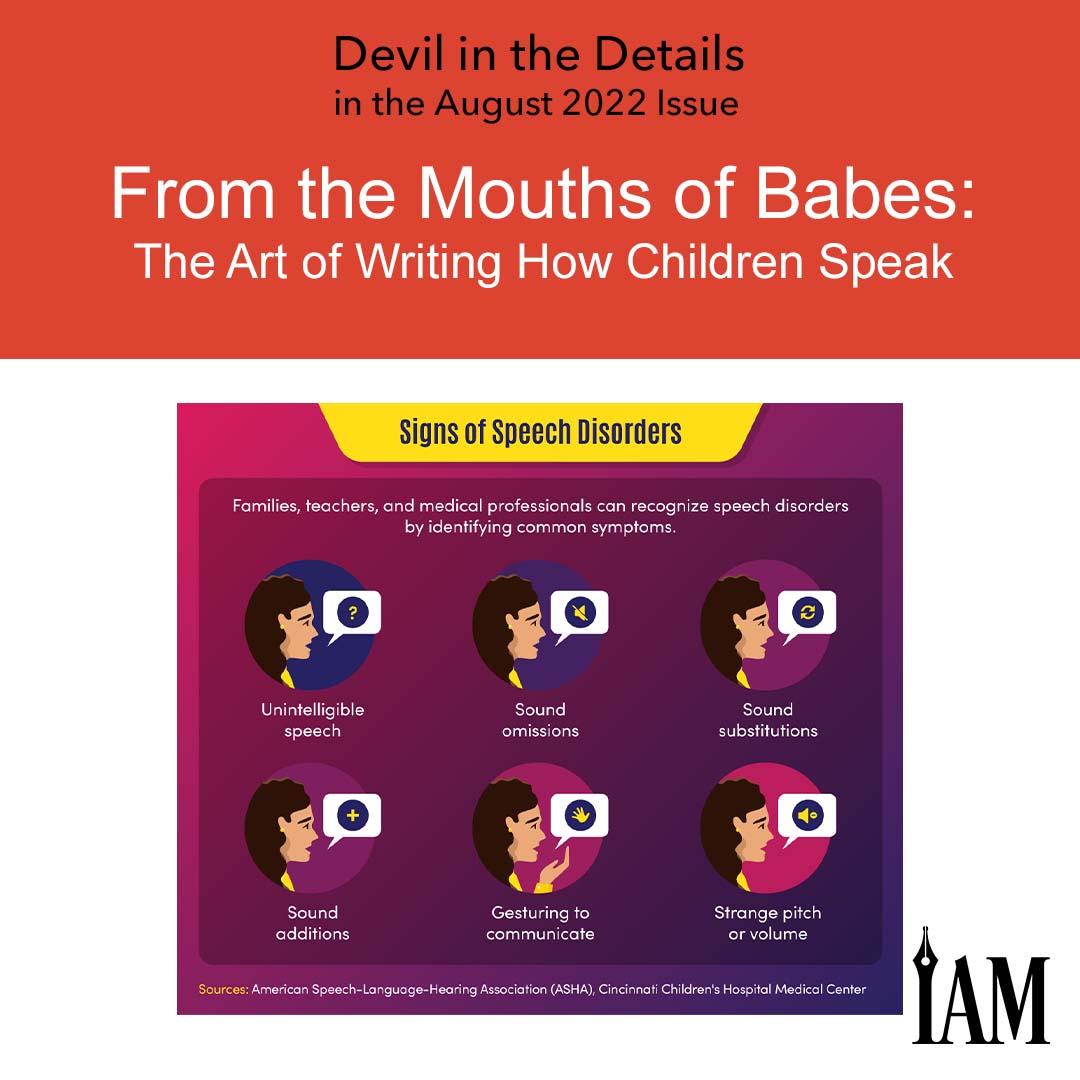

A Final Note: Speech Disorders and Other Disabilities

Not every child develops exactly along this timeline, so not every character needs to either. A toddler in your story with a disability, a stutter, or other speech disorder could regress in some milestones, meet them at a slower pace, or miss them entirely. It’s impossible to list specific symptoms for every diagnosis here, but according to Maryville University, common signs of speech disorders include sound substitutions, additions, or omissions; speaking in a strange pitch; or using gestures to communicate instead of words.

Infographic by: Maryville University.

Dialogue is never one-size-fits-all, even for younger characters, and sometimes a wise-beyond-their-years observation or an embarrassing question will be more believable than a mispronounced word. As with anything, do your research, and if it comes to it, don’t be afraid to draw from real-life experiences. After all, it’s not just a saying—kids truly do say the darndest things.

Nicole Schroeder