I opened the revisions file from my editor on my latest work in progress and was surprised by the number one item on her list. “The protagonist is launching a business!” she wrote. “Why isn’t she working on her website, having business cards made, handing out flyers—anything?”

I was slightly insulted. Of course, my character was doing whatever she needed to get her business off to a successful start. But there had just been a murder. Wasn’t that more important?

After I’d smoothed down my ruffled feathers, I realized my editor was right. I’d been so caught up in making my protagonist a sleuth that I’d neglected to make her human. I went back through the draft and made sure to show the character working on that website, ordering inventory, advertising, and becoming familiar with the neighborhood in which her shop was located.

The need for more mundane details doesn’t just apply to business ventures. Your readers want to know where your characters sleep, what they eat, and how they take care of their pets. If you’ve ever read a Cozy Mystery, you’ll know some readers care so much about what the characters eat, they insist on recipes being included at the back of the book.

If your character wandered through the desert all day and night with no food or water, he or she shouldn’t show up at a battle scene the next morning fresh, alert, and ready to fight. And if your protagonist is an alien or superhero who doesn’t need sleep, food, or water, you need to make that apparent ahead of time.

What Exactly Does Your Character Need?

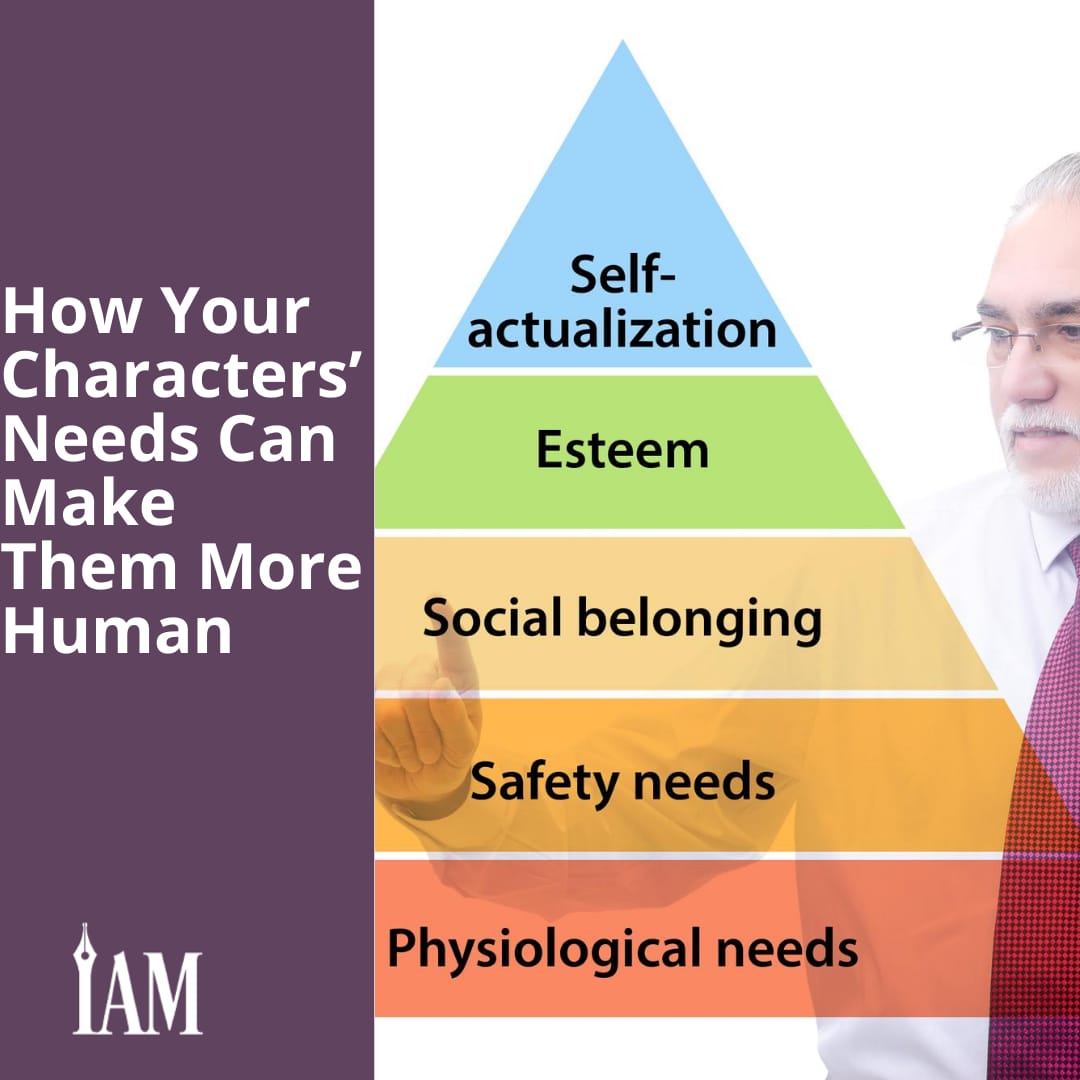

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a theory in the field of psychology proposed in 1943 by Abraham Maslow that suggests people will prioritize their most basic needs ahead of more advanced goals (https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html). The theory is most often depicted as a pyramid, with the bottom of the pyramid showing the basic needs—water, food, shelter, and sleep. Knowing how these needs, whether met or unmet, will affect your story facilitates your creation of a well-rounded character.

Look at the 2002 movie Insomnia. The detective in that movie suffers from sleep deprivation while investigating a murder in Alaska, and it drastically hampers his ability to solve the crime. Like with other physiological needs in Maslow’s pyramid, a character who cannot sleep will see those effects ripple outward into every other aspect of their lives, leading to problems such as stress, memory issues, and slower healing. And it won’t necessarily take much time for it to do so. Food can be as much a necessity as sleep for your characters, so make sure you give them a chance to eat and drink regularly. Of course, that’s if they have access to either—but if they don’t, it’s well worth checking out resources on the long-term effects of food deprivation and hunger, such as Natalie Silver’s breakdown of the question "How Long Can You Live Without Food?" on Healthline.com. Whether your protagonist is on a

diet or visiting a foreign planet and having trouble finding food compatible with his or her body, you need to understand how he or she will feel and think based on this lack of nourishment.

And if one of your characters is unhoused—temporarily or otherwise—consider taking a look at the February 2019 report, “Homelessness & Health: What’s the Connection?” by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (https://nhchc.org) to understand the effects a lack of shelter has on one’s physical and mental health.

The second tier of the needs hierarchy reflects safety needs. In modern day settings, perhaps most important is how your character makes a living. Is he living off his savings while he avenges his father’s murder? Is she married to an abusive billionaire and secretly looking for ways to escape? Is your character a child whose resources come from parents or other family members? In books that take place in more fantastical worlds, it might be more important to look beyond financial security. How does your character survive if your protagonist is living in a post-apocalyptic world or on another planet? Show your reader how your characters protect themselves and others—and what happens when they can’t.

In the center of the Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs pyramid, we have love and belonging. Character relationships are central to almost any story, but they’re also essential for understanding how your character experiences the world. Perhaps something has happened at the beginning of your story to stigmatize your character. In that case, show the reader your character’s aching need for acceptance. If your character is established in the community, then don’t forget to give them acquaintances. Even a lone lighthouse keeper would see a delivery person or regular angler on occasion. Alternatively, you might have characters who put the needs of their loved ones ahead of their own, such as in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. These choices, even if they aren’t acknowledged outright, can be especially impactful. By incorporating such scenes, you can illustrate the strength of certain character relationships to readers and make small moments, such as treating an injury or sharing a last bite of food, even more meaningful in the larger story.

Esteem and self-actualization are at the peak of the needs pyramid. Although esteem and self-actualization might not be paramount to your character’s survival, they are imperative to fleshing out your protagonist and gaining your reader’s empathy. It’s essential that you understand your character’s goals and motivations in a story, including how they might change, according to author E.M. Welsh. Welsh’s writing blog offers several resources for authors to use in order to better understand their characters’ motivations in a story. For even more resources and examples to help you determine your character’s goals, visit Bang2Write’s screenwriting blog post "23 Powerful Examples of Character Motivation" or explore the character motivation worksheet offered on “Lady Writer” Eva Deverell’s writing resources website (https://www.eadeverell.com/character-motivation/).

By incorporating your characters’ needs into your manuscript, you’ll be one step closer to making them feel real to the reader instead of wooden, two-dimensional pawns that exist just to drive your plot.